Climate change impacts are already being seen in species, habitats and ecosystems around the world – from shifts in species distribution, abundance and physiology, to species interactions and cyclical biological events like flowering, breeding and migration.

For human-centric industries like agriculture and urban design, climate adaptation is a rapidly growing field of research and has been integrated into operations and strategic planning. For biodiversity conservation, including wildlife conservation, the uptake has been slower.

A new IMAS PhD study published in Conservation Science and Practice has aimed to capture the breadth and richness of practical interventions underway globally to help wildlife adapt to climate change.

Lead author and IMAS University of Tasmania PhD candidate, Claire Mason, works on climate adaptation interventions for the shy albatross, such as artificial nests (pictured above), with researchers from IMAS, CSIRO and the Tasmanian Government.

“Our study came about because we knew others were trialing similar interventions around the world, and we wanted to learn from their experiences, to improve our climate adaptation work here in Tasmania,” Claire said.

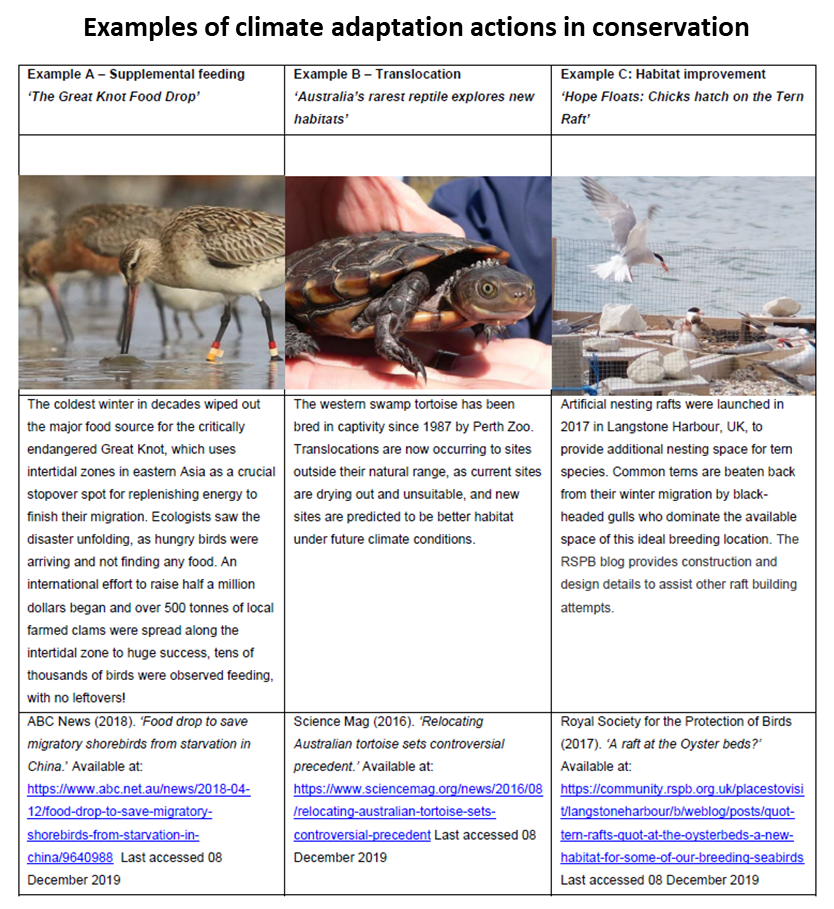

“We uncovered interventions like habitat modification, supplementary feeding, disease control and moving species into new locations, which may not all be directly related to climate, but have the objective of climate adaptation." (See table below)

“We uncovered interventions like habitat modification, supplementary feeding, disease control and moving species into new locations, which may not all be directly related to climate, but have the objective of climate adaptation." (See table below)

“Interestingly, we really struggled to find many of these interventions in the peer-reviewed literature, but we found a lot of examples in popular media such as on news websites, government media releases and blog posts by conservation organisations.”

Co-author and CSIRO researcher, Dr Alistair Hobday, said it is the first time these conservation practices have been synthesised.

“Our study clearly shows interventions are underway to help wildlife adapt to a changing climate, but they are not being evaluated or reported in a way that moves the field forward, based on robust and well-documented evidence,” Dr Hobday said.

“We found it was often a case of reacting to a real-time threat, such as an extreme event or food shortage, where a team who understood the species and the system well had created an innovative solution.

“However, climate adaptation will work best if the conservation action is proactive. Trials and experiments conducted while populations are robust will contribute to evidence-based interventions in the future,” he said.

The study’s recommendations for future adaptation interventions include sharing and publishing climate-related conservation interventions, using standardised metrics for reporting outcomes, implementing experimental controls for actions undertaken, and evaluating and reporting both failures and successes.

“It is vital to develop a ‘knowledge bank’ now, rather than relying on high-risk last resort actions when species are in serious peril,” Claire said.

Images:

Published 2 June 2021