Marine debris is globally recognised as a major threat to the environment, with an estimated 8-million tons of plastic debris entering the world’s oceans each year.

Growing public awareness of plastic pollution, and the problems it’s causing, has been informed by the work of scientists from around the world, including IMAS.

However, new research led by IMAS PhD student Catarina Serra-Goncalves and published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology has highlighted how inconsistencies in data collection and scientific methodology are hampering efforts to get a clear picture of the marine debris challenge.

The researchers compiled a list of 1060 scientific studies relating to beach debris and marine plastics published between 1980 and 2017, with 174 papers evaluated in detail. (Images: marine debris on Cocos Island. Credit, above right: Silke Stuckenbrock. Below, left: Jennifer Lavers)

Ms Serra-Goncalves said the study found that although plastic monitoring and research has intensified in recent years the lack of comprehensive datasets, combined with inconsistent methodologies within and across different studies, is clouding understanding of the extent of the problem.

“If we want to get a bigger picture of what is happening with marine and plastic pollution in our environments, scientists need to standardise their methodology and the way they report their findings,” Ms Serra-Goncalves said.

“But currently our understanding of this issue remains largely based on individual surveys reporting the abundance and type of beach debris at single locations.

“In the dynamic marine environment, these one-off surveys provide no information on changes over time, which can only be understood through robust sampling at the same site over many years.

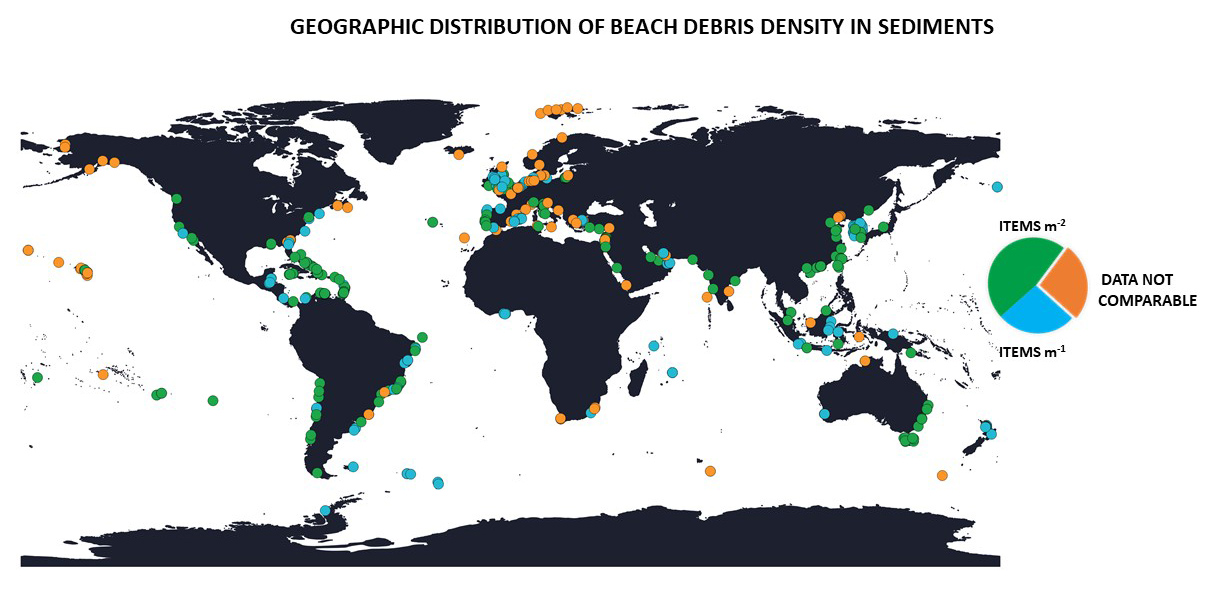

“More than one quarter of the studies we looked at reported their data in ways that cannot be compared or aggregated with other studies to form a bigger picture.

“Others failed to report basic important information, such as the date and precise location of sampling, the dimensions of transects, and the size of the debris collected.

“Understanding the geographical extent of the problem is also hampered by the fact that the majority of research is focused on only a handful of countries.”

“Understanding the geographical extent of the problem is also hampered by the fact that the majority of research is focused on only a handful of countries.”

Ms Serra-Goncalves said beach debris research requires significant improvement and standardisation, and would benefit from the adoption of a common reporting framework to promote consensus within the scientific community.

“To address issues with global impacts, such as plastic pollution, big datasets with a shared adopted

framework can play an important role

“As scientists, we need to be more aware about the importance of the data we are publishing, what we are reporting, and how we are reporting it.

“In other words, we need to start speaking the same language and working together towards a solution.

“If we don’t, we will not be able to understand what is happening, where it is happening and, most importantly, how we can solve it,” she said.